Cafés and nightclubs attain special resonance in times of great artistic or historical ferment. Jean-Paul Sartre’s Les Deux Magots helped birth existentialism; the pre-World War I Café des Westens in Berlin offered a gathering place to avant-gardists like Kandinsky and Marc; in 1940s Harlem, Minton’s Playhouse provided a venue for the new bebop developments in jazz. So it was in the Warsaw Ghetto that the Café Sztuka gained a special role in the lives of the closed district’s inhabitants.

In the spring of 1942, the newspaper Gazeta Zydowska described the Ghetto’s “public for theatres and concerts.” People went “above all, to the Sztuka. This was the most popular, most prestigious literary café, where the intelligentsia met. It was located at 2 Leszno Street. Many Polish-Jewish artists made appearances there, including the stars of prewar cabarets. In the Sztuka, Wiera Gran, Diana Blumenfeld, and Marysia Ajzensztadt sang. Wladyslaw Szpilman and Artur Goldfeder formed an excellent piano duet. In the Sztuka, Snow White was also staged for children."

The best known name among those listed is, of course, Szpilman, who survived the Ghetto, composed a memoir, and was offered far greater cultural familiarity by way of Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist.

Wiera Gran, or Vera Gran as Agata Tuszynska spells the singer’s name, was, like Szpilman, well-known to Poles before the war. Her earliest records were made in her teens under the name Sylvia Green, sometimes to an “orchestra of Hawaiian guitars.” In 1937, she toured Poland as a celebrity and earned substantial fees “making short advertising films” for lotions, soaps and colognes. Though her musical career was a Polish-language phenomenon, in 1939 she made use of her childhood Yiddish alongside Ida Kaminska in The Homeless, said to be the last Yiddish film made in Poland before the outbreak of war.

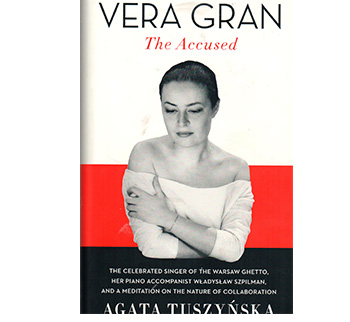

Tuszynska’s presentation of Gran’s story makes quick work of the singer’s prewar success. The story associated with Gran that drives the narrative of Vera Gran: The Accused derives from accusations, which first arose in the Ghetto but grew more ferocious after the war, that she used her popularity to create connections with the Gestapo.

Drawn into this tangled tale is Szpilman, with whom Gran performed at the Café Sztuka. And so the book’s lengthy self-description, which appears on its dustcover but not inside on its title page: “The Celebrated Singer of the Warsaw Ghetto, her Piano Accompanist Wladyslaw Szpilman, and a Meditation on the Nature of Collaboration.”

Tuszynska befriended Gran in 2003, when she was living as a near recluse, largely forgotten, in a cluttered apartment in “an elegant neighbourhood of Paris, the 16th, around the Eiffel Tower… An old woman, not very tall, in a pink dressing gown, opened the door a crack.”

They became an odd couple – meeting to record reminiscences and to struggle over how to understand the past – and Tuszynska stuck by her subject till the end, visiting her once when she moved to a home in the countryside dedicated to the care of Polish aged in France, and, finally, visiting her unmarked grave in a Paris suburb.

Tuszynska’s approach to her subject is greatly influenced by her uncommon access to and intimacy with Gran. The portrait we receive is of an alternatively angry, depressed, paranoid, even psychotic solitary figure, whose memories, though in many ways revealing, are marked by a sense of having been wrongly accused of collaboration.

There is almost nothing in the historical record to support this accusation. Tuszynska’s approach is to leave the question open, though she is ultimately on her subject’s side. There is an extended discussion in Vera Gran: The Accused of the nature of collaboration in the Warsaw Ghetto. The proposal is made, loosely supported by a side comment in the diaries of Emanuel Ringelblum, that spending evenings in cafés, whether as a performer, impresario or audience member, while children starved, was unethical. But Ringelblum’s criticism was aimed at the proprietors of certain cafés, who were in fact in contact with the Gestapo.

Tuszynska indulges the question of whether Gran might have considered that “practising her profession… could be inappropriate in this situation.” This runs contrary to the majority of historical writing on the role of the arts and culture in the major Nazi ghettos. In her monumental history of the Warsaw Ghetto, Barbara Engelking asserts the role of art, which, before the war, was simply “normal,” in the Ghetto became an “expression of dissent from the Nazi world order.”

Something untold or untellable seems to lurk in connection with Szpilman. For Gran, he is the key bête noir in her downfall, a figure lionized after the war who, she says, compromised himself as a Jewish policeman in the Ghetto. After the war, when Gran begged him for work in his Polish radio concerts, he denied her, based upon accusations regarding her wartime behaviour. Others backed him up. But, like Szpilman, they seemed to have a less than straightforward reason for doing so – something in their own wartime activities that made them fearful, even vengeful.

This aspect of Gran’s story remains shadowy. We understand that Gran was unduly accused, her career and possibly her sanity destroyed. The motives of her accusers remain vague, though Tuszynska does convey the complicated mindset of postwar survivors. Years after pointing the finger at Gran, key figures recant, while the damage continues as accusations reappear in Poland, in Israel and among survivors elsewhere.

Vera Gran: The Accused offers a counter-proposal to the notion that we can come to know another life, however public in its character, through careful research. The events of Gran’s life were chaotic; many of those who knew her, including her family, were murdered by the Germans; her treatment after the war was bizarre and troubling, a kind of trap she could not escape from. But out of these loose ends Tuszynska weaves a revealing narrative of Polish-Jewish identity, wartime experience, and, more importantly, the confusions and deceits lurking in postwar Holocaust response.