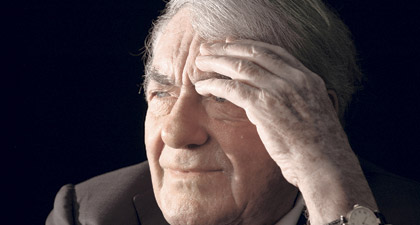

At 88, noted French intellectual, filmmaker, author and journalist Claude Lanzmann, who produced the classic documentary Shoah, has a new film that’s a tour de force. His latest documentary, The Last of the Unjust, rehabilitates the tarnished image of a very controversial witness to the Holocaust, Viennese Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein, the last head of the Jewish council (Judenrat) in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

The masterful, poignant film, which runs three hours and 40 minutes, recently opened in Canada.

In an exclusive interview from Paris, Lanzmann talked about the film and the man at its centre.

Why did you decide to devote a long documentary to such a controversial figure of European Jewry during World War II as Austrian Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein?

Benjamin Murmelstein was one of the first witnesses of the process used to exterminate European Jews that I interviewed when I began my research for the film Shoah. He was the only head of the Jewish Council in the Theresienstadt concentration camp who was not assassinated by the Germans during the war. He was the last chair of the Jewish council created by the Nazis in that ghetto [as the Germans liked to call it] located some 50 kilometres from Prague. His two predecessors in that unrewarding job came to a tragic end: Jacob Edelstein of Prague, arrested in 1943 and then deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and killed there, and Paul Epstein of Berlin, shot in the back of the neck in Theresienstadt in 1944.

At the end of the war, the Czech authorities and the leaders of the Jewish community – from which he was totally banned – accused Murmelstein of having been a “zealous collaborator in the pay of the Nazis.” In 1945, he was finally acquitted of the charges brought against him, after he had served an 18-month jail term. He could never go to Israel, where he was also a persona non grata. He died in 1989.

What did you find most intriguing about Rabbi Murmelstein’s very complicated character?

I really wanted to interview him, because I kept on asking myself what exactly a Jewish collaborator was. For me, there was a profound inherent contradiction in the very idea. I knew non-Jewish collaborators in France, in Belgium, in Holland… They totally embraced the Nazis’ ideology and anti-Semitism. Everything negative and hostile I had read about Murmelstein, including in the works of a major Holocaust specialist, the late American historian Raul Hilberg, left me very skeptical.

In Vienna, Rabbi Murmelstein was the only Jewish contact with the principal promoter of the Final Solution, Adolf Eichmann.

Yes, as chief rabbi of Vienna, Murmelstein found himself propelled, responsible for the Jewish community, charged with negotiating directly with Adolf Eichmann the emigration of the Jews of Vienna – a task he executed brilliantly because, thanks to his negotiating skills and his unwavering perseverance, 120,000 Jews were able to leave the Reich.

In your opinion, Rabbi Murmelstein was not a traitor, but a hero who used cunning rather than force to fight the Nazis.

Murmelstein’s predecessors at the head of the Jewish council in Theresienstadt, Jacob Edelstein and Paul Epstein, agreed to themselves draw up the lists of Jews who were going to be deported. That led to horrible negotiations, haggling and privileges. Those being deported put great pressure on the Jewish council head to have him remove their names from the list he had just established. Murmelstein categorically refused to play the macabre game. He told the Germans, with an unheard of courage, “You want to deport us, go make your lists yourself.”

The last witnesses of the Holocaust are disappearing. Was it the obligation to remember that motivated you to dedicate so many years of your life to documentaries about this horrible tragedy?

One thing is certain: it was not the obligation to remember that led me to make the film Shoah and other documentaries about that black period for humanity. We have been hounded a lot about the disappearance of the last witnesses of the Shoah. They are not all dead yet! And, when the last witnesses of that unspeakable tragedy have disappeared, at least one thing will remain – my films!

In France, high school teachers complain about the difficulty they have in teaching Arab students from the Maghreb (northwest Africa) about the Shoah. Are you aware of this problem?

It’s not true! It’s not difficult to teach the Shoah in French high schools. You just have to know how to do it. We have to train the teachers properly. I have been invited several times into schools reputed to be difficult, where the majority of the students are black or Arab students from the Maghreb. I showed the students my film Shoah, and then I spoke to them for about 20 minutes, basically to explain the difference between a concentration camp and an extermination camp. After having watched the scene with the hairdresser in the Treblinka camp, whom the Germans forced to cut the hair of women who were going to be gassed, several of the youngsters had tears in their eyes. They left this screening of scenes from Shoah with a mad desire to make films, too. There was not the slightest protest against my presence in those schools. On the contrary, I was welcomed very politely.