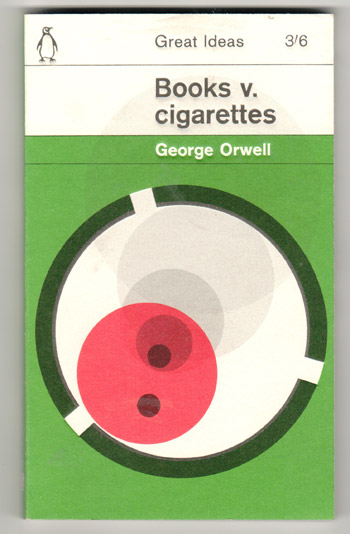

Books v. Cigarettes

George Orwell.

Penguin Great Ideas Series

Our access to books is changing apace. In a big city like Montreal or Toronto, it is increasingly difficult to find a bookstore with enough stock to allow for a good, revelatory browse. Libraries are refocusing their attention on new forms of public space, new venues for “knowledge delivery,” and consider moving book stacks off site.

Major book chains present, on the main floor of their landmark locations, not books, but household items – mugs, bath mats and candles. In the same way, the major online bookseller is awash in every product under the sun, while it follows the search patterns of book buyers in order to sell them pet food and appliances.

In Canada we think of the frailties of the book trade as being caused by our peculiar national economy and culture. For a few decades, beginning in the 1960s, the federal and provincial governments provided funding to programs that supported regional publishing. But much of this infrastructure has disappeared; American ownership of our large publishers is now de rigueur; a more-or-less monopolistic state exists in our book selling and distribution market; and the conglomeration of media ownership means that if a review runs in a major newspaper in Montreal, it will most likely fill space in its sister papers across the country.

It’s astonishing to open George Orwell’s collection Books v. Cigarettes, much of which first appeared in 1946, to find that trends we think of as of the moment were underway in Orwell’s London, 70 years ago.

In Orwell’s portrait of mid-’40s England he catalogues familiar woes. In the essay Books v. Cigarettes he comments on the prevalent notion that book buying is an extravagance, an overpriced habit. In his characteristically wry tone, Orwell computes his own book, newspaper and magazine buying costs to find that his expenditures in this area do not compete with his budget for Players cigarettes and a “half a pint of mild six days a week.”

“I have said enough,” he writes, “to show that reading is one of the cheaper recreations: after listening to the radio probably the cheapest.”

I could not help thinking, as I read Orwell’s tallying of his outlay on books and smokes, of an argument commonly expressed today to account for a preference for virtual books over the artifact previously known, simply, as a book: that is, that the former can be had more cheaply. How cheap, I wonder, when people say this, must a book be?

In an essay titled Bookshop Memories Orwell reflects on his work in a second-hand bookshop, mostly to characterize the precariousness of this sort of business.

Who does he highlight as his memorable customers at the shop “on the frontier between Hampstead and Camden Town”? There are the “not quite certifiable lunatics” who “gravitate towards bookshops, because a bookshop is one of the few places where you can hang about for a long time without spending any money.”

Our big chains have borrowed a page from this scenario, creating living room-style nooks where customers flip through things they may or may not buy. Even the throw rugs and mugs in major chain stores are reminiscent of what London second-hand shops peddled to pay their overhead: “second-hand typewriters . . . stamps . . . sixpenny horoscopes . . . in sealed envelopes.”

In Confessions of a Book Reviewer Orwell describes a literary predicament that is common today. The “standard of reviewing has gone down,” Orwell tells us, “owing to lack of space.” A possible antidote discussed at the time was that “a good deal of reviewing, especially of novels, might well be done by amateurs.” Here Orwell is prophetic of the use by Amazon of homemade reviews as no-cost product promotion.

As one would expect from the author of Homage to Catalonia and 1984, Orwell is concerned about the rarity among his contemporaries of engaged writing that is free of a party line. In 1946 when he published The Prevention of Literature, Orwell recalled the previous decade, when a Soviet mythos held sway over English intellectual life, and accounted for an unwillingness to speak or write forthrightly about pressing issues “like Poland, the Spanish Civil War, the Russo-German Pact” and the “twenty months” during which Hitler’s pact with Stalinist Russia held.

Orwell’s disgust with modes of totalitarian thought and language is timely, as we watch press events overseen by Vladimir Putin, in which pliant journalists take down the leader’s words as if they represent the world as it should be. The startling videos, viewable on YouTube, depicting Cossacks horsewhipping the musicians from the Russian punk group Pussy Riot, make Orwell’s characterization of totalitarian society prescient: “Such a society, no matter how long it persists, can never afford to become tolerant or intellectually stable. It can never permit either the truthful recording of facts, or the emotional sincerity, that literary creation demands.”

Here we have language that is nearly 70 years old, but which addresses, with great ethical vigour, the totalitarian character of life under Putin. One hopes there are Russian or Ukrainian novelists up to the challenge of a response, spurred by the dual images of Putin, legs spread, browbeating reporters, and the reappearance on the national stage of Cossacks wielding whips.

But there is shame in the fact that the entire Olympic theatre was acted out without a single substantial protest by athletes and their minders. In the mid-’40s, Orwell proposed that intellectuals who remained obediently silent alongside totalitarian violence “killed” books. Books v. Cigarettes reads today as a remarkable warning against such self-silencing.

Norman Ravvin is a writer and teacher in Montreal.