Few are the modern men who can be said to have been Shakespearean in their nature, their ways, their work and their legacy. The term, however, would apply to Ariel Sharon.

Revered as a hero, reviled as a villain, militarily skilled, militarily reckless, compassionate, brutish, a careful tactician, an uncaring bulldozer, a builder, a destroyer, an inspiring leader, a betrayer of promises, coarse, tender – all these descriptions and many more have been applied to Sharon, one of Israel’s – and the Jewish people’s – most compelling figures of modern times.

The famous general and prime minister died on Jan.11. Even in illness, as in his life, Sharon confounded his friends and foes. He “fought” to stay alive for nearly eight years after he fell into a coma in January of 2006.

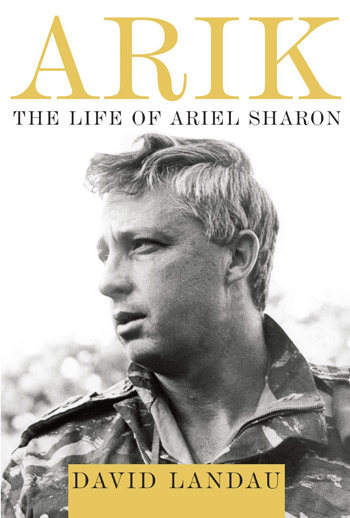

Thus it was a propitious coincidence of publishing that this biography by the Israeli journalist David Landau appeared just as Sharon’s suffering was reaching its humane end.

Landau has written a highly informative work that chronicles the more than eight decades of Sharon’s life. He paints a portrait of the grand figure with vast detail, paying meticulous attention to the myriad facts and opinions of the man that served as Landau’s canvas. The result is a superb recounting of episodes and incidents – on the field where armies clashed or in the Knesset where politicians did battle – that leave one shaking one’s head and catching one’s breath. Needless to say, those battles were the very same struggles and profoundly affecting upheavals that have shaped the Jewish state.

Landau brings to his subject considerable experience as a writer and a visibly patent dedication to his craft. He has a law degree as well as a yeshiva education and has been writing for more than four decades after starting with the Jerusalem Post in 1970. Since then, he was the founding editor of the English edition of Ha’aretz and then the newspaper’s editor-in-chief from 2004-2008. He still serves today as correspondent for The Economist. Landau has collaborated with Shimon Peres on his memoir, Battling for Peace, and on the book Ben-Gurion: A Political Life.

At the outset, Landau makes plain his left-leaning ideological orientation. It is the lens through which he views, assesses and explains the Israeli government’s policies toward the Palestinians, especially the frequently vaudevillian but always woebegone process of discussions, negotiations, cold shoulders, warm embraces, polemics, posturing, debating and hectoring that we have euphemistically called the peace process.

For example, in the introductory pages, Landau refers to the return of the Jews to parts of the West Bank after the Six Day War as “Israel’s misguided colonization of Palestinian territory.” He deliberately chooses a loaded and pejorative term to ensure the reader knows precisely where he stands on the issue of the “settlements.” Frequently, however, he sacrifices nuance and accuracy to make the more stinging political point compelled by his conscience.

There is no doubt that the Jewish settlements have become the sharply sharded scythe slicing away at Israel’s standing, even among its friends, but Landau’s blanket condemnation is excessive and unfair.

Setting aside for the moment the demographic, political, practical, ethical and moral concerns regarding Jewish communities in the heart of the West Bank, were Israelis not justified to return to the Old City of Jerusalem from which they were evicted? Were they not justified in returning to the hilltop south of Jerusalem that had been Kfar Etzion until 1948?

These questions are not merely rhetorical. They cut to the core of the century-old heartache that is the Israeli-Arab conflict: the rejection by the Arab League and the local Arab leadership of the right of Jews, as well, to be sovereign in the Middle East. However painful it might have been for them, the Jews did not reject the Arab right to sovereignty. The Jews did not launch a war against the local Arabs. The Arab League and the local Arab leaders launched a war of genocide against the Jews and their nascent state. Too often, Landau diminishes or evades the responsibility of the Palestinian leadership for the predicament of their people.

And yet, despite Landau’s up-front political stance, the book is a praiseworthy achievement. At 635 pages, nearly 100 of which are original source documents, footnotes and index, it is massively researched, superbly organized and heavy with information.

As both praise for Sharon and lamentation for his country, Landau tells us why he undertook to write this biography.

“What he began during the dramatic years of his prime ministership (2001-2006), contradicting a lifetime of military extremism and political obduracy, entitles him…to a place of honour in Israel’s annals. … When he was elected prime minister, many proud and patriotic Israelis talked seriously of leaving the country. His accession to power was the stuff of nightmares. The future seemed to hold only war and bloodshed. When he collapsed, less than five years later, we wept. Not just for him: for ourselves.”

In one of his last addresses to the Knesset during the debate on the Gaza withdrawal, his heart crying, the bold, enigmatic prime minister explained what he had come to believe was the best way to protect his beloved Israel.

“This decision is unbearably hard for me. In all my years as a military commander, as a politician, as a minister, and now as prime minister I have never had to take such a hard decision.

“I know full well what this decision means for the thousands of Israelis who have been living in the Gaza region for so many years …who built homes there and planted trees there and grew flowers and raised boys and girls who have known no other home. I know full well. I sent them.…I feel their pain, their fury, their despair.

“But as deeply as I understand what they are going through, I believe in the need to take this decision for disengagement and I am determined as deeply to carry it out. I am convinced in the depths of my soul and with my entire intellect that this disengagement will strengthen Israel’s hold on territory vital for its existence, will win the support and appreciation of countries near and far, will reduce enmity, will break down boycott and siege and will advance us on the path of peace with the Palestinian and our other neighbours.”

Nearly a decade after Sharon spoke these words and made the fateful decision to unilaterally withdraw Israel from Gaza, the peace he so determinedly sought is no closer at hand.

Landau’s book helps us better understand the man who was felled, alas, before he could walk the final way on that path of peace.