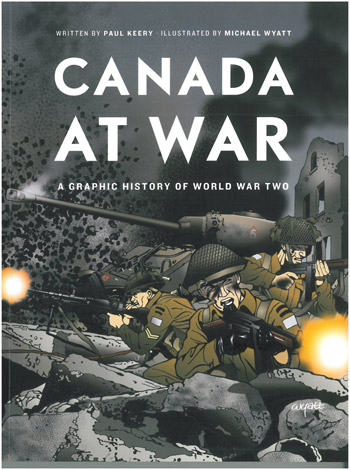

Canada at War: A Graphic History of World War Two

Paul Keery.

Illustrated by Michael Wyatt.

Douglas & McIntyre.

In the obituaries that followed Alex Colville’s recent death, many cited his experience as a 25-year-old war artist, riding through Germany in the spring of 1945 with the Third Canadian Infantry Division.

At Bergen Belsen, which was liberated by the British, Colville encountered emaciated survivors, including some who died in front of him, and heaps of the dead. He did sketches and watercolours, which, in the mode of other war artists hired by the Canadian government, he worked up as oil paintings when he returned home. Some of these are viewable on the website of the Ottawa War Museum, but these paintings aren’t generally on display at the museum itself. On the museum’s website, you can view a reproduction of the remarkable painting Bodies in a Grave, Belsen, in which many of the motifs of Holocaust imagery of later film and literature receive their first masterly presentation. Colville was among the first artists to address Holocaust atrocities.

War, as part of Canadian history, has played an increasing role in efforts by the present Canadian government to fund memorialization. Government-funded programs have focused on the War of 1812 as well as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, asserting the contemporary urge to do something more with events that helped define Canadian identity.

Canada at War: A Graphic History of World War Two is a contribution to this effort. Graphic presentations of difficult subject matter – one thinks always in this context of Art Spiegelman’s breakthrough, Maus – have become common in popular and educational markets. Although they’re aimed, first, at young adults, most adults find things to admire in them. Canada at War is lavish, large format, reliant far more on the punch of its images than on the detail or stylishness of its text. Here it differs from Maus, which Spiegelman chose to present in black and white, and which tells its story in rich novelistic language through the presentation of colourful characters.

Canada at War presents no characters. There are familiar faces – those of Mackenzie King and Hitler – but these are background figures to the larger patterns of moving fronts, key battles, setbacks and victories. Organized around major contributions by the Canadian armed forces, Canada at War outlines disasters at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Allied advance through Italy, Canadian successes in Germany and Holland, and, finally, the short-lived Canadian involvement in the Pacific. The reader learns how a weak, underfunded Armed Forces was massively increased in size and trained in drastic new challenges in order to aid in the defeat of Germany.

Some undertakings ordered by the Allied leaders are put in a critical light, including the high-casualty advance through Italy, whose military usefulness remains a point of contention. But Canada at War avoids any number of difficult issues, including the Canadian government’s inaction in response to the German-created refugee disaster in Europe, the impact of French Quebec on King’s attitudes toward conscription and the internment of Montreal Mayor Camillien Houde for sedition based on his support for Mussolini’s Italy as a Roman Catholic country. Rather, Canada at War highlights Quebec-based detachments fighting in Europe – and so it should, but alongside more troubling issues.

The need for war heroes appeared as soon as the war was on. Comic books were popular reading material among the forces, and back home, the Canadian Jewish Congress saw them as a medium well matched to the events in Europe. Prepared in 1944, comics under the title Jewish War Heroes told the stories of Col. David Arnold Croll, later the mayor of Windsor; Lou Warren Somers, who flew in the Halifax-based Lion Squadron, and Max Abramson, a native of Calgary, who, aboard the HMCS Prince Robert, was involved in the capture of a German armed merchant ship.

Drawn with a heavy black line, the CJC comics go for an action-packed, heroic look, not unlike that of Canada at War, though the latter has a penchant for high-colour images of artillery barrage as it rips through machinery and men. Canada at War zeroes in on heroes – winners of the Distinguished Service Order and leaders with visionary plans – much like the CJC’s choice of subjects.

The Congress comics were designed for schoolchildren to provide an education on developments in Europe and to lend an upbeat note to the dark events sweeping in on the radio and in newsreels. Canada at War is likely headed for history classrooms, where its focus on explosive battles, effective hardware and improved training will go over well. Its imagery is ripely dramatic for the video game generation.

At the War Museum in Ottawa, Colville’s postwar paintings present themselves as remarkable and wholly unheroic alternatives to the punch of the graphic story-telling in Canada at War.

Colville was always modest and matter of fact in his accounts of his encounter with Belsen. “For me, it was work,” he said. “If you’re a writer or a painter, your material is life as you see it being lived and that’s it. You get to work and do it.”

Norman Ravvin is at work on a collaborative book, The Wordless Leonard Cohen Songbook, with Toronto book artist and wood engraver George A. Walker.