Rabbi Yehuda Amital (1924-2010) was a compassionate, charismatic and occasionally controversial leader of the National Religious (or modern Orthodox) Jewish community in Israel.

A Holocaust survivor, he was liberated at the end of 1944. He moved to Israel right away and served in the Israeli army in the War of Independence. He pursued a career in Jewish education, and in 1968, became a founder and rosh yeshiva (head of school) of Yeshivat Har Etzion, one of the first institutions set up in the territories that Israel won in the Six Day War.

Partly because of the yeshiva’s location and partly because of the teachers and students it attracted, the yeshiva and Rabbi Amital were originally considered to be on the right wing of the Israeli political spectrum. However, in 1988, Rabbi Amital founded the Israeli movement Meimad, a short-lived political party of religious Jews who wanted Israel to take more courageous steps toward making peace with Palestinians, including territorial compromise.

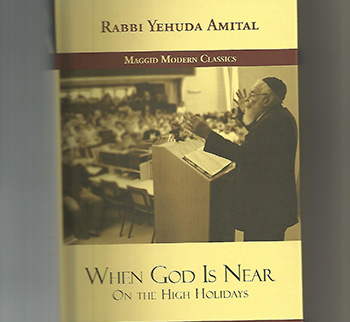

Many Jews knew Rabbi Amital best for his political involvement. But he saw his life work as being a rosh yeshiva. In an attempt to make this side of his life understandable to English readers, Maggid Books has published a collection of talks that he delivered to his students over the years during the High Holiday season. The talks were adapted and edited by his son, Rabbi Yoel Amital. A thoughtful afterword by his son-in-law, Rabbi Yehudah Gilad, discusses the philosophical and educational themes in the talks.

Taking the words of an Israeli rosh yeshiva speaking to his students and bringing them to life for non-yeshiva English speakers is not an easy task. The translator must have command of biblical, rabbinic and modern Hebrew, as well as Aramaic. Familiarity with the sources themselves is a must, since much of the discussion involves texts building upon each other.

Seven translators took part, although most of the work was done by Karen Fish. The result is almost always readable and accurate. Occasional lapses occur. For example, when Maimonides explains how God measures people’s righteousness, the Hebrew text reads: “The reckoning is not based on the number of merits and sins but on their magnitude.” (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Repentance, 3:2).

Here, Maimonides’ statement becomes: “The reckoning is not based only on the number of merits and sins but also on their magnitude.” Maimonides’ text does not require improvement or toning down.

Still, the book does successfully convey the values of this special rabbi. Readers see that he, unlike many other heads of yeshivot, did not teach his students to withdraw from the culture around them and concentrate only on Torah. He did not encourage or even allow his students to think that since they were involved in serious study of holy texts, they were superior to the rest of Israeli society.

A large portion of the book consists of Rabbi Amital’s explanations of the biblical story (Genesis, 22) of the binding of Isaac, when God tells Abraham to take his son Isaac to a distant mountain and sacrifice him there. Abraham complies, but at the very last moment, the tragedy is averted when an angel tells Abraham to stop. This story is a central part of the Rosh Hashanah service, and we will also be reading it again in synagogues in a few weeks.

The Bible tells us nothing about Abraham’s state of mind during the three days that he and Isaac were travelling to the site of sacrifice. Some religious thinkers have portrayed Abraham as a “knight of faith,” a term coined by the Christian thinker Soren Kierkegaard. Many think of Abraham as a silent paragon of faith and submission who follows God’s instructions dutifully even when he does not understand them.

Rabbi Amital rejected this interpretation. He repeatedly taught his yeshiva students that rabbinic Judaism understood the story of Abraham and Isaac differently, quoting the line from the Mishnah (Taanit, 2:4) that says that in Temple times, people offered the following prayer on fast days: “He who answered Abraham at Mount Moriah – may He answer you and listen to your cry on this day.” (A version of this line has survived as part of the Slichot service in use today, too.)

Rabbi Amital pointed out that this meant the ancient rabbis understood that Abraham did not accept God’s command silently. Rather, he beseeched God to spare Isaac. This point is also made in other old rabbinic texts. Rabbi Amital often quoted this one as well: “His [Abraham’s] eyes opened with a great weeping, and he sighed a great sigh… and said, ‘I lift up my eyes to the mountains; from where shall my help come?’” (Yalkut Shimoni, 1:101, quoting Psalms, 121:1).

“We are familiar,” Rabbi Amital taught, “with the phenomenon of the suppression of any human or parental feeling while in the throes of religious ecstasy. In biblical times, this found expression in the worship of Moloch, and in our times, we see the attitude in the response of our neighbours to the death of a ‘shahid’ [martyr].” According to Rabbi Amital, Abraham passed God’s test by not giving up on his human parental feelings. Jewish tradition, he taught, “seeks to emphasize the humanity of Abraham.”

Human feelings and emotions, Rabbi Amital taught, are not at odds with religious behaviour, but are an integral part of the practice of Judaism.