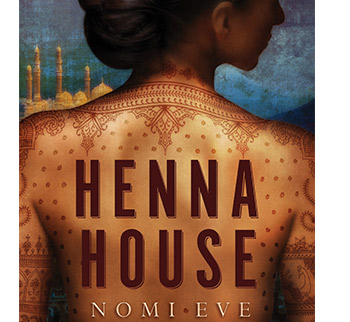

Henna House casts a spell.

Through vividly described images, powerful, evocative tugs upon the senses and a narrative that is brazen and tender, numbing and pleasurable, sorrowful and delightful, Nomi Eve effects a form of literary hypnosis upon the reader. The work releases its grip only with the turn of the last page.

This is quite a remarkable feat since the narrator, Adela Damari, recounts her story in retrospect. At the outset, she foreshadows in very broad terms where the story will eventually lead. No matter. How it transports us there is the magic carpet we ride back in time, witnesses to the life Adela lived intensely, passionately, vulnerably, dutifully, and finally, courageously.

Henna House is a historical novel. The story sweeps through large epochal events of the 20th century beginning with the narrator’s birth in 1918 in the northern hillside town of Qaraah, Yemen. Compared to the larger cities of Sana’a and Aden, Qaraah was relatively untouched by modernity. Indeed, its residents led a style of life essentially unchanged from the lives of their forebears long ago. Women were mostly illiterate. Amulets, charms, secret codes, and fear of the evil eye were mainstay features of everyday life. In addition, there was the inescapable sense of oppression of Jews, an officially tolerated religious minority, by a frequently intolerant majority.

The terrain and landscape of Yemen – religious, cultural, social, political, and geographic – hovers over virtually every page of the book. Only after Damari is carried “upon eagle’s wings” to the nascent State of Israel, in the last portion of the book, are we freed of the danger that lurked constantly around the corners of the Jews’ lives in Yemen.

Although Adela is the creative fulcrum upon which the dramatic events of the story hinge, Eve also creates arresting portraits of other vivid, memorable characters. Many compelling figures such as her aunt Rahel and cousin Hani, both masters in the art of henna dyeing, play significant, determinative roles in Adela’s life.

In Qaraah, the rules of separation between men and women were unambiguous. The two sexes intersected primarily in two domains: at the table and in the bedchamber. In part to enhance relations in the bedchamber, especially the newlywed chamber, the use of henna was a pivotal aspect of women’s lives. The custom is ancient, exotic, sophisticated, complex and purposeful.

Eve uses henna as a narrative reference point and as a metaphor, as a literary device and as a symbol. She artfully portrays the nature of intra-communal relations among Jewish women in Yemen by emphasizing the importance for those women of the use of henna privately and collectively at intimate moments in their lives. For them, henna is a practice, an idea, and an esthetic underlying human existence. In a note at the end of the book, the author acknowledges the research sources she used to convey the significance of henna in the lives of Yemeni women. The Henna House in the title refers to the elaborate social conventions surrounding the application of the henna.

The narrator explores her gradual metamorphosis as she, too, learned how to apply henna. “Each sign had a corresponding connotation. A squiggle was a wave in the ocean, but it was also a cupped palm, a gesture of greeting, or of harvest plenty, or both…Learning how to apply henna made me look at the world differently. Where before I had seen pebbles, pine needles, blades of straw, I now saw shadows and lines that were the sinew and bone of pictures yet to be drawn.”

Adela’s voice matures over the course of the story. She interprets the circumstances and the events that unfold through the multi-faceted prism of her traditional female role in the home, under the authority of her parents, under the ominously looming cruelty of the laws of Moslem Yemeni society and under the influence of her extended family.

For example, Hani asked Adela: “‘Do you think Musa hits her to give her pain, or to give himself pleasure?’

“I balked, ‘What do you mean? What a horrible thing to say.’ I was blushing.

“‘Well,” Hani said, ‘clearly she covers her face to hide bruises, and she doesn’t appear in public so people won’t gossip about her injuries. And when a man hits a wife, sometimes it is for punishment, but sometimes it is to open the gates of paradise. For him, I mean. For her? Well a man’s paradise can be a woman’s hell.’”

In myriad ways, Eve gives expression to universal “women’s issues” as experienced by the Jewish women of Yemen. But this is merely one aspect of the story that is impressive.

Eve has also provided a cultural history of the Jewish life in Yemen that no longer exists. In addition, she places in a broader Middle Eastern context the emergency migration of the Jews from Yemen to the newly established State of Israel. Her reflections are wide-ranging and offer poignant insights into the binding ties of Jewish peoplehood.

During the Damari family’s harrowing flight from Qaraah to Aden, Adela notes: “I found myself wondering in whose steps we were following. I also wondered how we could learn to read the marks left by ancient travelers on the stones of this earth.” Eve is clearly hinting to us that the story she has written in the voice of Adela Damari is intended to ignite higher flames of personal inquiry among readers.

When she arrives in Israel and is questioned by well-meaning, but insensitive, bureaucrats about the belongings she brought to her new homeland, Adela acknowledges “the only true possession I brought with me from Yemen was this story.” As the years pass by and Adela builds a new life for herself, she struggles to find a way to properly honour the sanctity of the memories of the family she once had. Her husband encourages her to write her memoir because “souls live on in stories.”

This is Eve’s second novel. Her first, The Family Orchard, a Book-of-the-Month Club main selection, was nominated for a National Jewish Book Award. Eve teaches fiction writing at Bryn Mawr and lives in Philadelphia with her family.

The souls of Adela Damari’s family populate the Henna House. It is a place worth visiting