Lynda can recall the very moment she gave into her then-husband’s psychological and emotional abuse, giving him total control over her life.

“It was a situation when we were moving into our apartment and my parents were helping me in the apartment. He came home from work – this was before we were married – and he said, ‘You have to choose, it is either me or them.’”

She chose him.

Lynda, who was married to her ex-husband for 13 years, said the abuse and the control he had over her started small and gradually escalated.

“I started becoming what he thought I should be rather than staying true to myself and along the way I lost my voice,” Lynda said.

“I had three kids by the time I was 30. By that time, he controlled everything. He controlled the money, he controlled every single thing. He even kept track of my menstrual cycle so he knew when we could have sex.”

Lynda’s account is one of many Jewish women’s stories of abuse suffered at the hands of their husbands.

Sadly, Jewish families are just as susceptible to domestic abuse as those in any other community.

“For most people in our community, they don’t believe it happens to us. They believe the Jewish community is immune to such things, because of our tremendous value on family and shalom bayit,” said Penny Krowitz, the executive director of a non-profit organization that partners with Jewish Family and Child Services called Act To End Violence Against Women (ATEVAW).

According to the Jewish Coalition Against Domestic Abuse, one in four women experience domestic abuse during their lifetime and abuse occurs in the Jewish community at the same rate as in the community at large – about 15 to 25 per cent of families.

“Understanding what abuse looks like is so important,” Krowitz said.

“There is a lack of understanding of it in the Jewish community, and I assure you that for all the women we know about, there are that many more who are living in abusive relationships. I’ve had women say to me, after I’ve spoken at a sisterhood event, and they’ve said, ‘Oh my God, I never knew it was called abuse,” she said, adding that women often think that if their husbands aren’t hitting them, they’re not being abused.

Domestic abuse can be defined as an imbalance of power, when one uses threats or physical force to create fear, control or intimidate another.

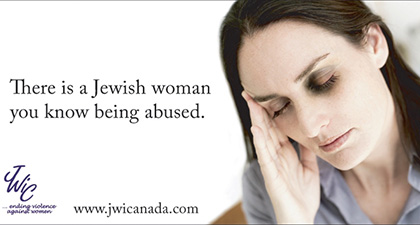

In 2006, ATEVAW launched a campaign to raise awareness about domestic abuse in the Jewish community by erecting billboards along Bathurst Street in Toronto.

The billboards portrayed a woman with a black eye and read, “There is a Jewish woman you know being abused.”

“Our goal was to portray all Jewish women, but not to have a woman who was all beaten up, because the majority of abuse is verbal, emotional, psychological, financial, spiritual, sexual – it's not visible abuse,” she said.

“The night before it went up I didn’t sleep all night. I thought, ‘The community is going to kill me,’ to be honest with you,” Krowitz said.

“We did get the comment, ‘How dare you air our dirty laundry in public…’ That was sad. But the best phone call I got was from a woman who said, ‘I thought I was the only one.’”

Krowitz said raising awareness about the issue, and dispelling myths about what abuse is and is not, is central to the work she and her colleagues do across the country.

Diane Sasson, executive director of Montreal’s kosher women’s shelter, Auberge Shalom Pour Femmes, said the percentage of clients who are Jewish at the shelter is about 20 per cent, and about 35 per cent for its external services for women who aren’t living in the facility.

Sasson said that now more than ever, people understand there are many types of abuse.

“Even in the more Orthodox world [which tends to be more traditional and insular], there is more of an understanding that there are many forms of abuse… I think there has been progress… but we still have tons of work to do, because while there is a better general understanding… The problem is not gone,” said Sasson, who has been running Auberge Shalom for the past 20 years.

“There is more awareness, but the problem itself is still festering. I think it’s about men having permission to be the stronger one in the relationship, and I believe that the patriarchal line [of authority] is still there. So yes, there is more awareness, but I don’t think the change has been made.”

Despite leaving her abusive husband 13 years ago, Lynda only learned about ATEVAW last year, and has been volunteering with the organization ever since, in the hope she can help other women who need support.

When she left her husband, “I didn’t reach out because I didn’t know that anything was available. I came from a family where you didn't talk about that stuff. I mean, I watched abuse all my life between my parents – verbal, emotional and sometimes physical with my parents. That was my life. I didn’t know any different,” Lynda said.

“I remember talking to my mother-in-law [about domestic abuse] and she would say, ‘Oh it doesn’t happen – there’s no abuse in the Jewish community.’ And I’m sitting there thinking, ‘Yes there is.’ I hadn’t yet identified it in my relationship with him, but I knew that I had grown up with it.”

Krowitz said the general feeling on abuse is that it happens to somebody else.

“The image people have is that it happens to a family that is quite poor, uneducated, heavy drinking, drug use – that’s the family that has abuse going on in the relationship, so people are shocked to learn that there are no socio-economic barriers,” she explained.

“One of the myths is that all Jewish families are loving, nurturing and harmonious… I’ll say something very unpopular – shalom bayit is a double-edged sword. When you have it in your home it is wonderful, and that’s what we strive for, but sometimes it becomes a barrier for a woman, because she is ashamed that her home is not a place of peace and she feels like it is her fault.”

She said one of the biggest barriers to seeking help is the concept of the situation being a shandeh – “the shame of admitting, disclosing, that your home is not a happy place. That your husband doesn’t treat you well, that you are frightened, that you walk on eggshells.”

Krowitz said the community needs to talk freely about the issue.

“I think we have to talk about it and break down the shame and recognize that… everyone has the right to live in a peaceful, content life and be mutually respected.”

For more information about services available to women coping with domestic abuse, contact ATEVAW at 905-695-5374; Jewish Family and Child Services at 416-638-7800; or Auberge Shalom’s support line at 514-731-0833.