Where do you feel most at peace in the world?

Take a moment to think about that special location that never fails to put you at ease. For some, it might be a cottage, a lake or a beach. For others, it might be a synagogue or another Jewish institution that allows them to feel connected to their Hebrew brothers and sisters across space and time.

Yet for many Canadian Jews of colour, finding peace in a Jewish space is not a realistic option. They are too used to having their Judaism constantly questioned, if not outright doubted. They speak of having to keep their guard up every time they enter a new Jewish space, because too often, somebody does something to make them feel unwelcome.

That can be as innocuous-seeming as asking if they’re Jewish. But over time, the weight of all the questions add up. Some Jews of colour begin to question their own Jewish identities and whether they belong in Jewish spaces at all.

Although the people interviewed for this story understand that the motives behind such questions are innocent, even the best-intentioned of these queries can reinforce the idea that people of colour don’t belong in Canadian Jewish places.

“That’s not how you start a relational conversation, so that’s why it’s a problem. And I know that if I didn’t look the way I did, they would not ask that question,” said Rivka Campbell, a black Jewish woman who works as a synagogue administrator in Toronto and, in her spare time, leads presentations about Jewish diversity. “Do you want to set up a conversation where they have to explain to you why they belong where they are?”

Many Jews of colour have learned not to take such questions personally and do not see them as an insurmountable obstacle to engaging in their religion. They have many positive interactions and experiences in the Jewish world, and the religion plays a large and important role in their lives. But they still find it tiring to have to prove their credentials over and over, and worry about their brethren who may not be as well-equipped to handle the endless interviews.

“When people question my Judaism, they do it maybe for the first five to 10 minutes and then realize who they are talking to – a yeshiva boy that probably knows more than all of the doubters combined,” said Eliran Penkar, an Israeli-Canadian Jew of Indian descent who studies mechanical engineering at Dalhousie University. “When the doubters see that, they don’t question as much.… Now, if the person is not as knowledgeable, it would be a very easy target. It’s basically a David and Goliath scenario.”

Even Penkar, whose family members were leaders of the Mumbai Jewish community for generations and who describes himself as “a very vocal Zionist and very vocal Jewish advocate,” became less observant and felt less connected to the community when he first moved to Canada. Penkar was born in India, moved to Israel when he was six and came to Canada when he was 13. He has lived in Calgary, Victoria, Toronto, Sydney, St. John’s and Halifax.

But between the ages of 13, when he moved to Calgary, and 22, when he moved to Toronto, he felt constrained in his ability to practice his Jewish faith for a variety of reasons. In Toronto, he finally connected with his family and a community of other Indian Jews, which rekindled his passion for Judaism.

When he left Toronto to move out east, he once again struggled to find that same kind of connection. It’s not that people actively excluded Penkar, but that he didn’t feel like there was room for him to practice Judaism as he knew it.

“Anything that is not part of the status quo, per se, is pretty weird and the aspect of acknowledging traditions from around the world is not as embraced in Western culture as it likes to think it is,” he said.

Eventually, Penkar joined the Halifax chapter of the Jewish fraternity Alpha Epsilon Pi. For the first time since he moved from Toronto, he felt like he was able to identify as an Indian Jew, rather than a Jewish person who happened to be Indian. Before that reawakening, he felt like “a golem of golems. (I went) basically from being in one of the loneliest places to being normalized.”

Penkar would like the repeated questioning of Indian Jews and other Jewish minorities in Canada to end, but he understands why the practice persists.

The majority of Canadian Jews are Ashkenazic and it’s natural for them to be curious about the unfamiliar, he said.

When his family moved to Israel, they were questioned by authorities in that country and had to fight to prove their Jewish identity, despite their historic devotion to Judaism and India’s Jewish community. Eventually, though, as Israelis got used to Indian Jews and as the relationship between the two countries strengthened, his family’s Jewish identity was accepted. That’s why he believes that the best way to move forward is to educate people about the diversity of the Jewish people.

READ: CHECK YOUR JEWISH PRIVILEGE

Diane Tobin also believes that education can unite the Jewish people. Tobin and her late husband Gary researched racially diverse Jews in the United States, after adopting their African-American son Jonah 21 years ago. When they realized that many Jews of colour felt isolated within their communities, they eventually started an organization called Be’chol Lashon, which teaches Jewish-Americans that the Jews are a multicultural people who live pretty much everywhere.

Be’chol Lashon runs camps that teach about different Jewish cultures and helps Jewish schools and institutions form curriculums on Jewish diversity, among other programs. Tobin said that Jewish organizations are increasingly interested in initiatives like Be’chol Lashon, as identity politics have increasingly come to the fore and the Jewish community has struggled to find its place in the conversation.

“I think Jews, given our history of persecution, we certainly want to be on the right side of history. And now we certainly find ourselves, in the politics of race in America, on the white side. And that doesn’t capture the Jewish experience,” said Tobin.

“We certainly benefit from privilege, but our history is not one of being white-privileged people. So that’s something the Jewish community is very aware of and very much wants to understand better.”

For Tobin, whose son is a young black man living in America, it’s also a very personal issue. “My privilege does not protect him,” she said.

The concept of white privilege, as it applies to the Jewish community, is a contested one. Many Jews do not identify as white and reject the idea that white privilege applies to anyone who is Jewish.

It can feel wrong to claim white ethnicity when white supremacists explicitly, and often violently, exclude Jews. But it’s also clear that darker-skinned Jewish people have to face obstacles both within and outside the Jewish community that their lighter-skinned counterparts don’t have to contend with, and sometimes may not even realize exist.

That’s why Tema Smith, the director of community engagement at Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto, prefers terms like “functionally white” or “conditionally white,” which she thinks better account for the complexity of the Jewish experience. It’s a way of acknowledging the historic persecution and exclusion of all Jewish people, as well as the relative advantages of having light skin in our society.

Smith has a black father and an Ashkenazic Jewish mother, but with her fair skin, curly dark hair and glasses, she looks, in her own words, like a stereotypical Ashkenazic Jew. As a Jew of colour who often doesn’t have to defend her Judaism the way other Jews of colour do, one of her goals as a Jewish professional is to “make the community a comfortable place for people of colour to be Jewish.”

She’s heard countless stories of Jews of colour being interrogated over their Judaism, and even stories of being profiled by synagogue security or mistaken for the staff.

“Different people have different appetites for how many times you have to explain yourself when you walk into spaces. So I think for me, when I think about what it means to build a community where people are going to be comfortable, what it means is educating the people in those spaces,” she said. “And I’m not just talking about the rabbis and professionals. Educating the Jews that are in the spaces that the Jewish religion has always had room for racial and ethnic diversity.”

She also wants Jews of colour to be recognized as individuals, rather than as a bloc. She’s noticed a recent trend of people making assumptions about all Jews of colour: “That they are politically similar, religiously similar and everything else. And that’s very far from the truth.”

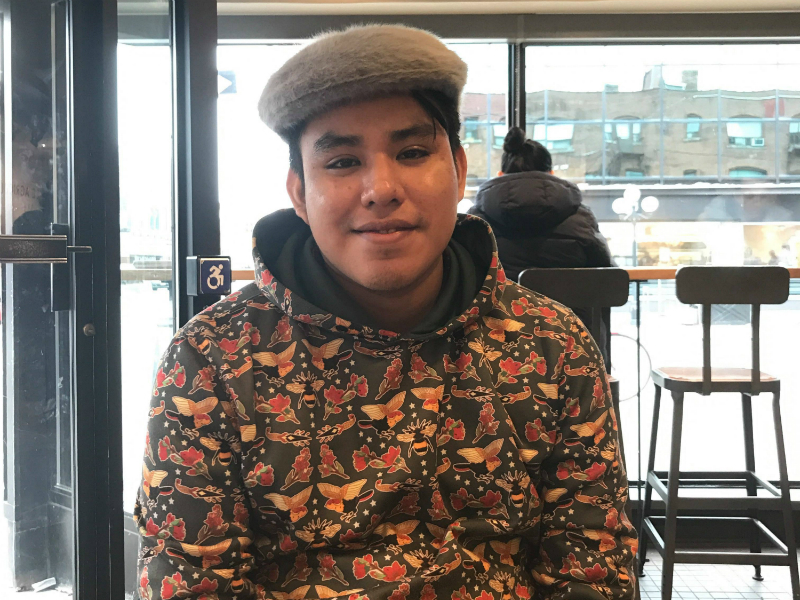

The assumptions can be more harmful than political or religious generalizations. Jobim Novak, a Jewish Torontonian of Guatemalan descent who was adopted as a baby, was once entirely rejected as a Jew due to his ethnicity: at one point in his life, he and a Jewish girl were romantically interested in each other, but she ultimately scorned him because she said he wasn’t a real Jew.

“I felt more angry than sad, because I feel a deep connection with Judaism. It’s everything I can remember, from five months old to now. I’ve been Jewish my whole life, even if I was not born into it,” said Novak, whose Twitter handle is “The Mayan Lion of Zion.” “I’ve always felt like this is my religion. I’ve chosen it, I was raised in it and this is the religion I want to bring to a family when I start a family.”

Novak has also dealt with less overt discrimination over the years, the same kind of doubt that other Jews of colour have had to endure. It’s part of the reason he feels like something of a nomad.

“I haven’t really been to shul very often and I think maybe some of that was in part due to feeling uncomfortable, though I hate to admit it. But that’s probably a reason, subconsciously, that’s been there for years. But I also feel like there are other ways that I can worship ha-Shem,” he said. “You can be a good person and a good Jew without necessarily going to synagogue all the time.”

When speaking about his experiences as a Jew of colour, Novak does not sound bitter and does not paint every interaction he’s had within the Jewish community with the same brush. In fact, he’s been invited to speak at Temple Sinai next month and feels optimistic about one day finding his place within Toronto’s Jewish community. But he remains aware of the cumulative effect of negative interactions based on assumptions or ignorance.

Yet even Jews of colour are not immune to jumping to conclusions about other Jews of colour, as Moshe Modeira learned about himself over a decade ago. Modeira is the son of a north African Jewish woman and a Jewish-Ethiopian rabbi. He was born in Toronto and spent parts of his childhood in Israel, Switzerland and Sweden, before moving back to Toronto when he was eight. That was the first time he faced North America’s unique brand of anti-black racism, which helped shape his worldview.

Even so, it didn’t entirely prevent him from judging other people based on their race. One day in 2005, when he was living in Israel and working for the mayor of Eilat, an Asian man wearing a kippah came to his table, carrying a child in his arms who was also wearing a kippah. Then he spoke to Modeira in Hebrew.

“His Hebrew was much better than mine. But until he opened his mouth, I had this in me, I was like, ‘What is he doing here? This doesn’t gel with my experience. Why does he have a kippah on?’ … After he spoke to me in Hebrew, I was transported back to my first experiences in the Toronto Jewish community when I was so taken aback by people questioning my faith because of my skin colour,” he said.

“That I could turn around and do that to this person, I understood that this is not to be taken personally, this is a matter of contact and experience. And the more that we break bread with each other, and we learn, is the only way.”

Over the past two years, one Vancouver woman of Asian descent has had to learn the hard way about the barriers to her full participation in the Jewish community. The woman, who requested that she remain anonymous, decided to convert to Judaism after attending a Jewish wedding of a non-Jewish friend who was marrying a Jewish man.

“It was such a joyous celebration. And since then, I wanted to discover more,” she said. “I just loved everything about it: the holidays, a lot of the wisdom that you can get from Jewish studies and also the community. I really liked that sense of community and I decided to take the plunge.”

That sense of community has at times been harder to access than she expected. She is now used to being questioned, challenged and openly stared at during services. At times, she’s tried to converse with other women at Jewish events and been dismissed, sometimes because they assumed she was the help. “I try not to think about it too much.… I usually kind of push my Jewishness a bit more than normal,” she said. “I also have learned to be more assertive. So if people ask me, ‘Why are you here,’ or ‘Why are you converting,’ or whatever, I tend to ask a few questions back. Sometimes people get offended and they don’t understand that asking those kind of questions is personal, so if you’re going to ask me that, I’m going to ask you back in the same vein.”

Instead of immediately asking personal questions, Campbell, the synagogue administrator and presenter on Jewish diversity, advised that people try offering personal information as a way of building bridges.

Campbell recognizes that Jewish geography and heritage is an important way that Jews communicate, especially when they first meet, and she doesn’t want Jews of colour to be excluded from that conversation. It would only isolate Jews of colour further if other Jews decided not to talk to them for fear of causing offence.

“It’s all about your approach,” said Campbell. “It’s etiquette. It’s manners. It’s how you wish to be treated, you treat others.”

Campbell points to an interaction she had with a man at a Jewish wedding as a case study in respectfully engaging in conversation about Jewish heritage. The two introduced themselves and the man immediately started telling Campbell about himself, which put her at ease.

When he asked her where she was born, and she told him that she’s from Toronto, “it led me to tell him more about myself. And the conversation took a great turn because I told him that my background is Jamaican, and he said, ‘Oh my God, I love Jamaica.’ And then the conversation switched to talking about Jamaica,” she said.

“His approach was perfect. Asking me about my family kind of softens it, because we all come from different countries.… It wasn’t, ‘Are you Jewish, how did you become Jewish,’ it was, ‘Where’s your family from?’ ”

Another important point that made the conversation respectful from Campbell’s point of view was that the man assumed she was Jewish, as opposed to assuming she wasn’t. Even when she’s in a Jewish space wearing Jewish garb, people still sometimes default to the assumption that she isn’t Jewish because she’s black.

That’s why her interaction with the man at the wedding was so refreshing. He didn’t force her to prove she was Jewish and didn’t treat her like a curiosity.

“He was genuinely interested about me as a person, and not just my story,” Campbell said.

And that’s perhaps the biggest takeaway from listening to the experiences of these Canadian Jews of colour. They may be discouraged or exhausted from enduring the same treatment over and over again, but that doesn’t mean they are discouraged about Judaism as a whole, or angry at the people who constantly doubt them. They are inspired by Judaism and want to do their part to improve the Canadian Jewish experience for everyone.

Many remain hopeful that increased exposure and education will reduce the questioning and perceived novelty of Jews of colour over the long-term. In the meantime, they hope that sharing their experiences will help teach all Jews about how to respectfully interact with others from across the cultural and ethnic spectrum.