Unlike many children of Holocaust survivors, Bernice Steinhardt, 67, and her sister were never sheltered from the horrors their mother, Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, experienced as a teenager during the war.

The sisters grew up in Brooklyn, hearing vivid accounts of their mother’s struggle to survive, as well as happy tales of her childhood in Poland.

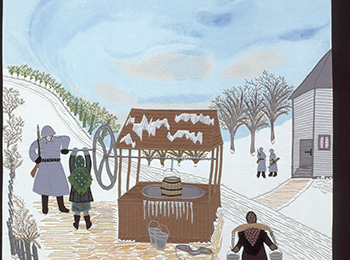

These stories, told through a series of photographs of Krinitz’s hand-crafted, richly woven tapestries, will be showcased in an exhibit called Fabric of Survival at Toronto’s Temple Sinai Congregation from Oct. 29 to Nov. 23.

The exhibit marks both Holocaust Education Week and the synagogue’s 60th anniversary.

Krinitz, who died in 2001, had a unique survival story: the Nazis occupied Mniszek, her small Polish village, in 1939. In 1942, they ordered all the Jews to report to a train station in a nearby town.

The night before leaving, Krinitz begged her parents to think of a non-Jewish friend who could take her in. Her father had been a horse trader and had made a number of Polish friends during his travels. They agreed that she and one of her sisters should go to a friend of his in a nearby village, and the girls set off, never to see their parents or three other siblings again.

The man whose home they ran to only took them in for a few days, fearful the Nazis would kill them all.

Realizing she and her sister had no hope of surviving as Jews, Krinitz concocted false Polish, Catholic identities for them and they eventually found a village to work in.

In 1944, when the Soviets began pushing the Germans out of Poland, Krinitz, then 17, joined the Polish army and went to fight in Berlin. After the war, she went back to Poland to find her sister, and the two ended up in a displaced persons camp, where both met their future husbands. They eventually immigrated to New York.

Amazingly, Krinitz only began creating art in later life.

At age 50, she decided she wanted her daughters to see what her childhood home and her family members had looked like.

She had never drawn in her life, but could “sew anything,” Steinhardt said, having worked as an apprentice to a dressmaker as a young girl.

“She took a large piece of fabric and sketched onto it an image of her family’s house and their neighbour’s house, and started filling it in with stiches,” Steinhardt recalled. “It was quite beautiful, and she was really satisfied with it. It looked her to like what she saw in her mind’s eye.”

Krinitz gave this first tapestry to Steinhardt and made a companion piece for her other daughter, Helene McQuade.

It wasn’t until 10 years later that Krinitz felt inspired to create more, eventually sewing close to 40 elaborate panels depicting poignant scenes of village life before the war, the Nazis’ invasion of her town and expulsion of the Jews, the terror of being on the run, brushes with death, and her eventual liberation and escape to America.

For years, Steinhardt, who lived close to her mother, lovingly hung each tapestry on her wall, but she eventually “ran out of wall space,” and decided the artwork deserved a greater audience.

A year after Krinitz died, Steinhardt and McQuade founded Art and Remembrance, an art and educational non-profit based in Maryland, to share their mother’s creations and story of survival, and to use the panels as an educational tool.

For more than a decade, they’ve toured Krinitz’s tapestries, either the originals or large-scale photographs of them, in museums across the United States, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

The exhibit makes its Canadian debut at Temple Sinai, and will be accompanied by the screening of a documentary, Through the Eye of the Needle, which Steinhardt and her sister made about their mother. Steinhardt will speak at Temple Sinai on Nov. 9.

“We realized this [exhibit] was a very powerful way to bring the lessons of the Holocaust into the modern world, to convey them to the generations that are still learning them,” Steinhardt explained. “Because [the tapestries] feature the story of a young girl, they bring the war and the experience of the Holocaust to a very intimate level, and have the extraordinary power to inform and to move.”