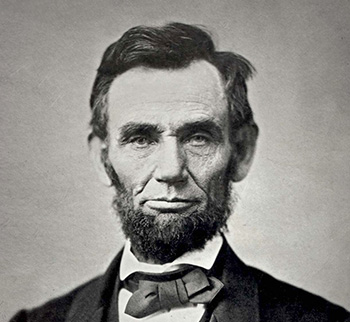

April 15 marked the 150th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, consistently rated as one of the top three U.S. presidents – and rightly so. Lincoln preserved the Union during the U.S. Civil War and abolished slavery. He was deserving of all the accolades bestowed upon him including the imposing statue, the focus of the grand Lincoln memorial in Washington, D.C.

Lincoln, somewhat strange (as he himself conceded) and peculiar-looking, was not without his flaws. He freed the slaves, yet very much a product of 19th-century thinking, he did not believe in the equality of the races.

At the same time, Lincoln had an enlightened attitude about Jews, especially for that era.

As Benjamin Shapell, the founder of the Shapell Manuscript Foundation and co-author with American historian Jonathan Sarna of the new illustrated book, Lincoln and the Jews, puts it: “He represented Jews, befriended Jews, admired Jews, commissioned Jews, defended Jews, pardoned Jews, consulted with Jews, and extended rights to Jews.”

In 1809, the year Lincoln was born, there were only 3,000 Jews in the United States. At his death in 1865, that number had increased to about 150,000, mainly emigrants from Great Britain and German states. It would take until the latter part of the 19th and early years of the 20th centuries and the mass migration of east European Jews before there was a true Jewish presence in America. Still, from the start, prejudice and discrimination against Jews existed despite their small number.

While Lincoln, who spent his early years in rural towns in Kentucky and Illinois, likely did not encounter a Jew until he was an adult, he came to know and befriend several. One of his closest confidants was Abraham Jonas, a fellow-lawyer and legislator.

Born in England in 1801, ‘Abe’ Jonas had immigrated to the United States in 1819, and together with his brother Joseph, had founded Congregation Bene Israel, “the oldest synagogue west of the Alleghenies” in Cincinnati. Though Jonas’ parents were Orthodox, he was not observant. “He delivered speeches on the Jewish Sabbath, ate non-kosher foods, and on at least one occasion in 1854, dined openly with Abraham Lincoln and others at an ‘oyster saloon,’” Shapell and Sarna write. Most notably, Jonas was an astute politician and played a key role as an adviser in Lincoln’s presidential campaign of 1860. In February of that year, some months before the election, Lincoln wrote to Jonas that: “You are one of my most valued friends.”

Another Jew Lincoln admired was his podiatrist, Dr. Issachar Zacharie. The same day that Lincoln signed the preliminary draft of the emancipation proclamation abolishing slavery, he also took the time to compose a reference letter for his friend. “Dr. Zacharie has operated on my feet with great success, and considerable addition to my comfort,” the president wrote. During the war, the talented and trusted Dr. Zacharie was sent on a secret peace mission in the south. While in Louisiana, the well-connected foot doctor learned about Confederate military strategy and troop strength, information that he passed on to Lincoln.

Apart from being the first president to appoint Jewish chaplains and seven Jewish generals, Lincoln’s most important decision involving Jews was to cancel Gen. Ulysses Grant’s notorious edict of 1862, which expelled all Jews from Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi on the pretext that Jews “as a class” had violated the Union’s trade regulations.

On scant evidence, Grant had determined that Jews were illegally selling southern cotton (despite the war, the trade continued, but it was regulated by the army). After Lincoln was besieged by telegrams from Jewish leaders and then met a group at the White House in early 1863, he revoked the order. “I do not like to hear a class or nationality condemned on account of a few sinners,” Lincoln declared.

An avid student of the Bible, Lincoln dreamed of visiting the Holy Land. According to his wife, Mary, the president spoke of travelling to Jerusalem in the carriage ride to Ford’s Theatre on the fateful evening of April 14, 1865. As they sat down in their box for a performance of Our American Cousin, Lincoln said softly to Mary, “how I should like to visit Jerusalem.” He never did.

Historian Allan Levine’s most recent book is Toronto: Biography of a City.