Toronto architect Benjamin Brown (1890-1974) designed many elegant edifices across the city, including the Balfour and Tower buildings on Spadina Avenue, the former Primrose Club on Willcocks Avenue, the former Beth Jacob Synagogue on Henry Street, the Hermant Building (eastern tower and annex) in Dundas Square, and scores of residences, theatres, factories, hotels and low-rise office and apartment buildings.

Possessing a trove of about 1,500 of Brown’s blueprints, drawings and renderings, the Ontario Jewish Archives (OJA) Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre has launched an $80,000 fundraising campaign to conserve and digitize his somewhat precarious paper legacy as well as to celebrate his significant but largely unsung contribution to Toronto’s urban fabric.

Towards the latter end, the OJA is preparing to spotlight Brown’s works in an exhibition in a prominent city venue, possibly the Gladstone Hotel, in the spring of 2016.

“The idea is to show the recently conserved drawings that will help explore Benjamin Brown’s process,” said OJA director Dara Solomon. “The larger narrative – what we really want to do with this exhibition – is to position Brown as one of Toronto’s important early architects, because he died in obscurity.”

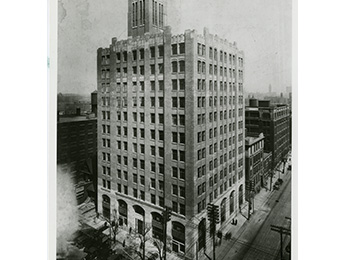

Brown’s art-deco Balfour Building and his Tower Building, which salute each other across the Spadina-Adelaide intersection, are considered the architectural gateways of Spadina Avenue. The city has designated both buildings, along with the Beth Jacob (now a Russian Orthodox church) and the Hermant and Commodore buildings, as heritage properties.

One of Toronto’s first Jewish architects, Brown began his career soon after graduating from architectural school in 1913, initially in partnership with architect Robert McConnell. He did much of his work for the Jewish community and seems to have attained his professional peak during the 1920s and 1930s.

Upon his death, Brown left his entire life’s work to Jim Levine, a fellow architect and friend. When Levine went to Brown’s home to retrieve the drawings, he found – according to a brief essay by Levine’s son Jay – “a dusty and deteriorating collection piled around, on top of and even inside of an old Edsel.”

Levine stored the collection for 13 years before offering it to the Centre for Canadian Architecture in Montreal. They rejected it, dismissing Brown as “a minor regional talent.” Next Levine contacted the OJA’s then-director Stephen Speisman to see if there was anything worth saving. “When Dr. Speisman saw what we had, he could hardly contain his excitement,” Jay Levine writes.

Brown’s works include the Brunswick Avenue Talmud Torah, the Rubinoff department store, the Old Spain restaurant for Lazar Levinson, a fur factory with apartments for the Schipper brothers, renovations for the Beach Hebrew Institute and McCaul Street Synagogue, and numerous service stations, warehouses and garages.

He also drew posh residences for Louis Gelber, Mendel Granatstein, Henry Greisman, Samuel Lavine, Ira Levy, Mandel Mehr, Sophia Rochman, Morris Spring, Irving Stone, Jacob Tenenbaum and many other clients. These are among the roughly 150 projects, large and small, represented in his prolific and varied oeuvre.

Brown also dabbled in theatres but, contrary to urban legend, he may not have had a huge part in the design of the Standard Theatre, the storied Yiddish theatre that opened in 1922 at the northeast corner of Dundas and Spadina. (Later a movie theatre and burlesque house, the heritage-designated structure now houses a bank and some shops.) Although Heritage Toronto names Brown as the architect– as did the Globe in a glowing account of the theatre’s opening – the dozens of detailed blueprints in the Brown collection bear the unmistakable architectural imprint of J. M. Jeffrey.

Based in Toronto early in his career, Jeffrey left in the early 1920s for the United States, where he participated in the design of such buildings as the Sherry-Netherland and Pierre Hotels in New York, and the Biltmore chain of hotels.

Did Brown only put the finishing touches on the Standard after Jeffrey’s departure? “It’s a bit of a mystery,” concedes archivist Donna Bernardo-Ceriz as she carefully unfurls some of the Standard’s delicate blueprints on a large table. “We’re hoping that an architectural historian will be able to fill us in on that.”

This is the fourth in a series of articles to be published periodically about Toronto’s Jewish institutions, funded by the J. B. & Dora Salsberg Fund at the Jewish Foundation of Greater Toronto. This series is in partnership with the Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre and draws on their collections: www.ontariojewisharchives.org